I introduce myself: my name is Gábor Domján.

A good friend of mine Tamás, great photographer, homepage guru, etc, is making this homepage for me. He’s the angel in the painting above nudging the lady to start playing her lute.

Being a dilettante (meant to mean: lover of arts) musician and aborted poet + translator of literary works, I am translating to Hungarian for years now all kinds of old songs as a hobby. These are chiefly lute songs from the renaissance era since I consider the lute to be the most beautiful instrument and the music of this age simply the loveliest. The reason for this later one might be that I feel in this age the so called ’light’ or popular music and classical music were one. Music wasn’t meant to be ’performed’ to bored audiances in concert halls. It was real life of real people really alive. Real music.

I also think only live music is music. Accordingly, it’s a dubious project to record and publish these songs. Life is being present: it comes, it’s here, it’s gone. A recording only ’is’, but for ever. A corpse. Nice and clean at times which might help to get one charmed (that is: I’m not belittling phantastic recordings of great artists – just some thoughts on the genre in general). However, life brings along the possibility of making mistakes. No problem: it came, ’twas there, it’s gone. A dead recording brings along the same mistakes for ever. Yet, I record everything in one go, and then I’ll choose from the many ’one-go’-s the one with the least technical errors. Or rather the one that succeded to be the most alive.

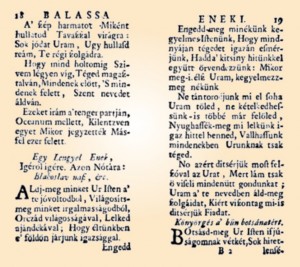

Translating songs is also questionable. It might look only the silly hobby of a silly person at first sight. There’s something to it: who cares for this stuff? However, this practice is well based I think. For example our poet Bálint Balassi (1554-1594) wrote in front of his poem ’Áldj meg minket Úristen’ (’Bless us Oh God Almighty’): ’A Polish song from verb to verb’ (meaning: same as a Polish song). And his poem is very true to the original, can be sung correctly prosodically, that is: a literal translation in the modern sense of the word. But apart from this, melodies, songs, poetical themes wandered freely and were transformed locally and into the local languages as well. There are many samples for this in the renaissance age.

The most importan part of a song is its text, the poem itself, even if it cannot be separated from the music most of the times (ie.: can hardly stand as a poem on its own). The concept of ’poem to the eye’ (or to the brain) is a novelty only a couple of hundred years old. And a poem – in most cases – can only come through directly when heard in one’s own native tongue I believe. For this reason I might happen to include some non-Hungarian translations as well (though translating poetry to other language than one’s own is a capital crime I’m afraid – nevertheless, here’s one such crime I have already committed, sung by Jeni Melia and accompanied by Andras L. Kecskes: Magos kősziklának / On a stony high cliff).

These are the causes of my humble experimenting. Thank you for listening to the songs. If I could bring along some joy with them I got my reward. If not – I beg your pardon.

GD