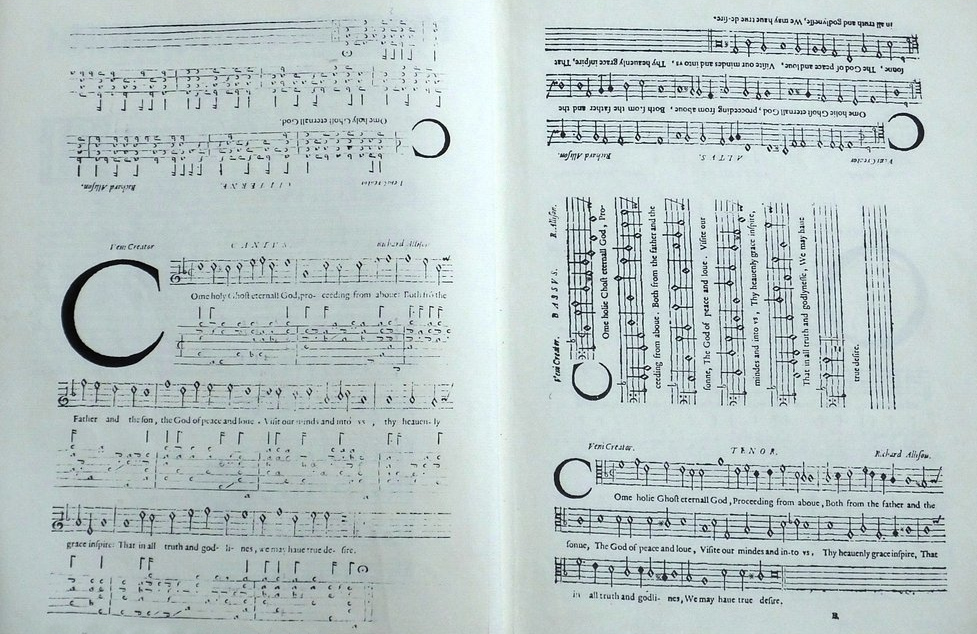

Richard Allison: Come Holy Ghost

Come holy Ghost eternal God,

Proceeding from above:

Both from the Father and the Son,

The God of peace and love.

Visit our minds and into us,

Thy heavenly grace inspire:

That in all truth and godliness,

We may have true desire.

Jöjj, Szentlélek, túlcsorduló

Egy örök istenség,

Atya s Fiú közt áradó

Szeretet, békesség!

Jöjj, látogasd meg lelkeink,

Hadd gyúljon égi láng,

S víg kedvvel járjunk jó utat,

Mely végén vár hazánk!

Hungarian translation by Gábor Domján

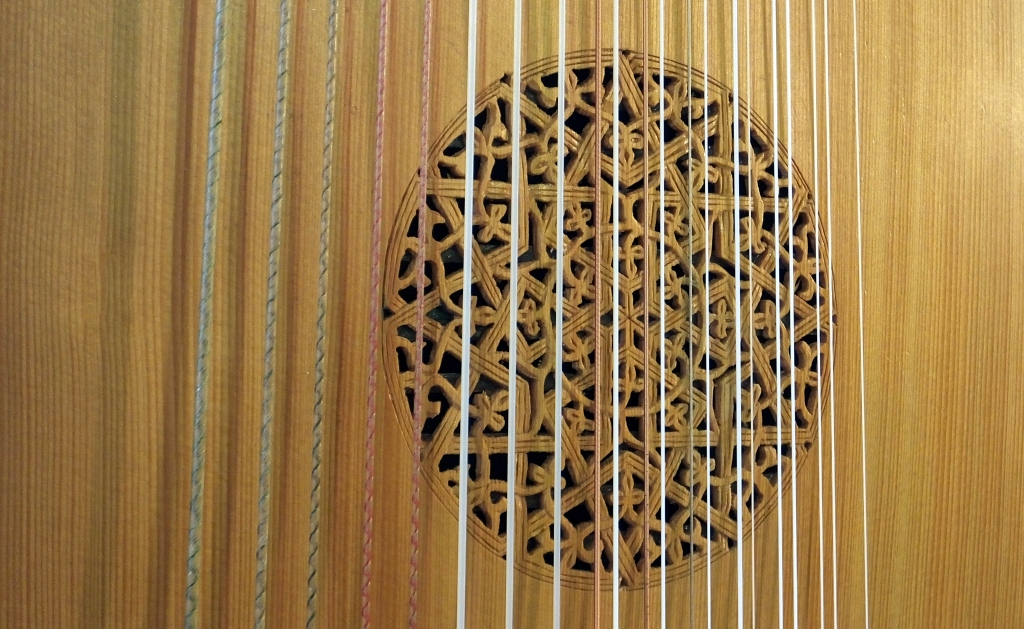

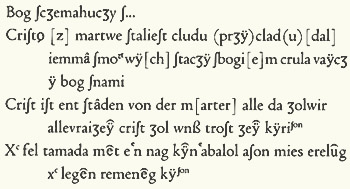

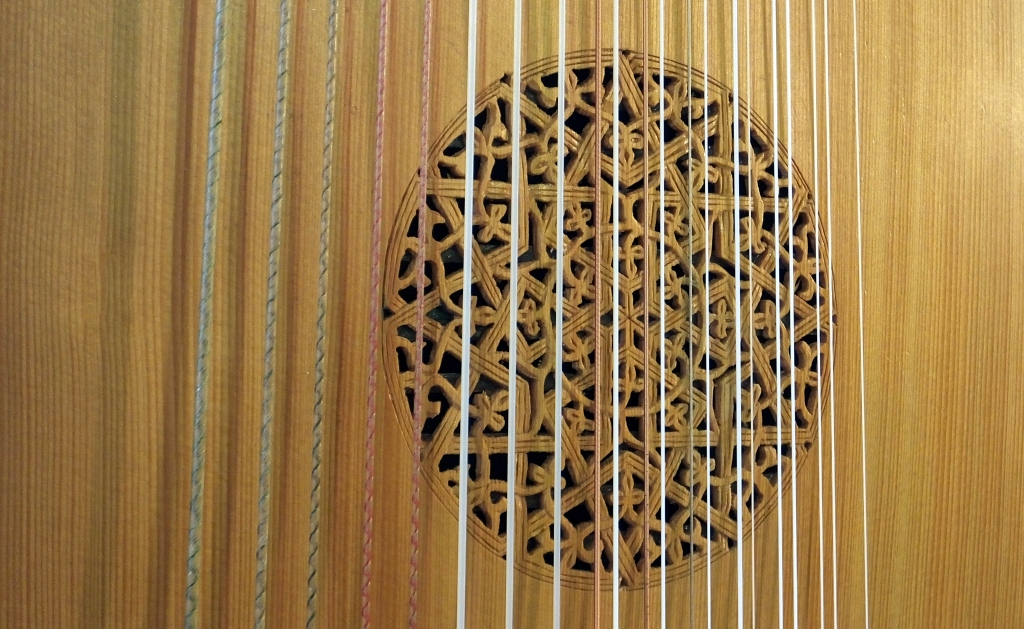

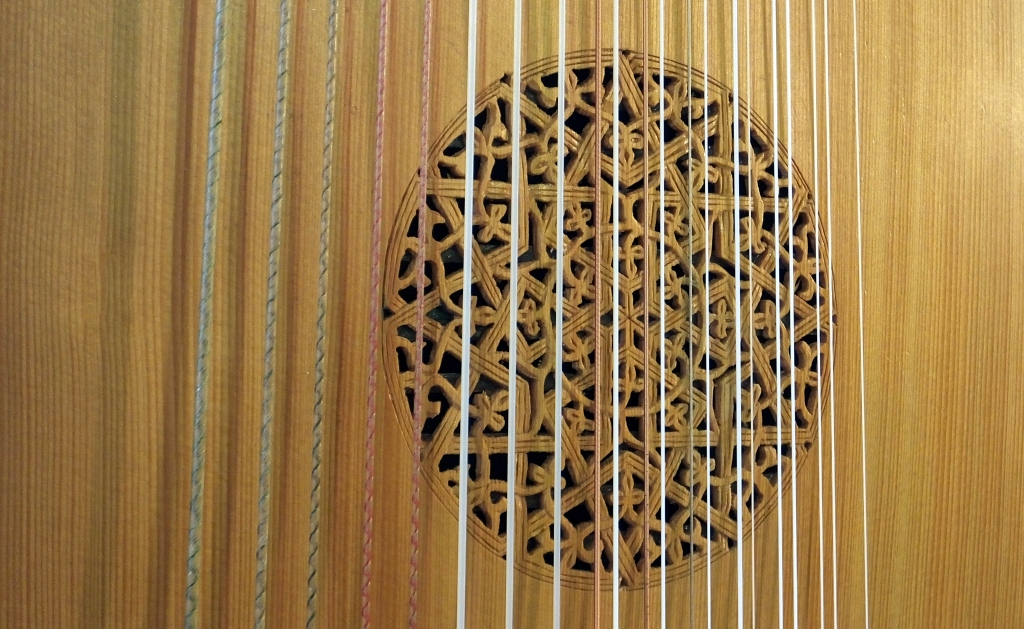

ARCHLUTE

copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 1999. The original instrument: Wendelin Tieffenbrucker (1551-1611, Padua), Brussels (M.I. No 1563).

Richard Allison (~1560/70 – died before 1610) was a gentleman as he calls himself ”Gent. Practitioner in the Art of Musicke ” on the first page of his work published in 1599 ”The Psalms of David in Meter”.

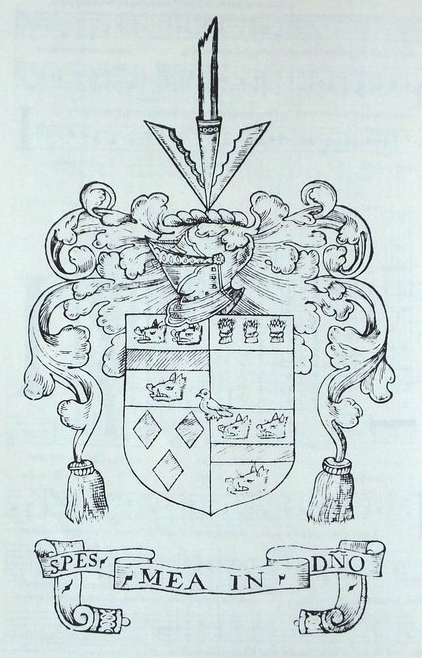

Supposedly it is his coat of arms on the back cover and there is also a poem by John Dowland praising the author and his pieces.

Boldogasszony anyánk (Joyous Lady our mother), folk song

download wav * download mp3

.

I heard this folk song from Erzsébet Török in the first years of the 1970-ies. This, or its variants are sung at rural parish-feasts, most likely in Transylvania too where she came from. The term ”Joyous Lady” for the Virgin Mary is a Hungarian speciallity as far as I know coming perhaps from the pagan times, referring to the pagan goddess of our predecessors, the phrase somehow surviving a millennium of christianity.

I heard this folk song from Erzsébet Török in the first years of the 1970-ies. This, or its variants are sung at rural parish-feasts, most likely in Transylvania too where she came from. The term ”Joyous Lady” for the Virgin Mary is a Hungarian speciallity as far as I know coming perhaps from the pagan times, referring to the pagan goddess of our predecessors, the phrase somehow surviving a millennium of christianity.

Erzsébet Török was a fantastic singer. I loved her singing very much. If my poor memory serves me well I sang this song at her funeral in 1973.

(continued below in the “Notes >>>” )

Boldogasszony anyánk (népdal)

Boldogasszony anyánk, mennyei pátrónánk,

Ha nem jössz, elveszünk, ha nem jössz, elveszünk.

Gyászba borult egek, háborgó tengerek

Csillaga, Mária, csillaga, Mária.

Nagy kiáltásokkal, könny hullajtásokkal

Hozzád kiáltozunk, hozzád kiáltozunk.

Hajnal szép csillaga, anyánk, szűz Mária

Hozzád fohászkodunk, hozzád fohászkodunk.

Joyous Lady our mother (folk song)

Joyous Lady our mother, our heavenly patron,

If you don’t come we perish.

Mournful skies, furious seas,

Thou art the star over them Mary.

In great cries, our tears falling endlessly,

we keep on shouting to thee.

Beautiful star of the dawn, our mother Virgin Mary,

to Thee we sigh.

(non-literary, verbatim translation)

ARCHLUTE

copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 1999. The original instrument: Wendelin Tieffenbrucker (1551-1611, Padua), Brussels (M.I. No 1563).

The lyrics of this folk song is sung here the same way as my memory serves me today. I just couldn’t find the original. Should I find a publication of it later I sure will paste it somewhere here.

However, this might be an apt example of the nature of folk songs and of ”poetical themes wandering freely and being transformed locally” as I mentioned in the introduction. The singer remembers something, somehow, and sings it freely.

The lute accompaniment of this song is based on the chords of András L. Kecskés.

Some more personal addendum on the pretext of Erzsébet Török: Zsuzsanna Gedényi writes in her memoirs („Csillagom, révészem – Török Erzsi tükre”, <Püski Kiadó, Budapest, 1997>)

„One of our acquaintances had a tumbledown old Tatraplan car. Far not everybody had a car those days, privately owned cars were rarities indeed. This kind gentleman offered to give a lift to the singer lady… … all in all, we had two more punctures coming home from the country so we arrived back in Budapest at haf past seven in the morning.”

I believe this „kind gentleman”might have been my father. Not only had he a tumbledown Czech Tatraplan at the end of the 50-ies, but he also knew many artists of that age personally. I also have a memory of my mother crying and quarelling early in the morning why my father didn’t phone her (of course, there were no public booths on highways, nor did simple people like us usually have a phone at their homes in the communist era). It might have been this occasion I believe.

My father was a truly good father. I sing this song to him, to Erzsébet Török and to every soul who have already passed this transitional physical world – that is, to the community of saints – commending them and all of us still alive here into the mercy of God, using the symbol of parental love – the Joyous Lady Mother – for the love of God.

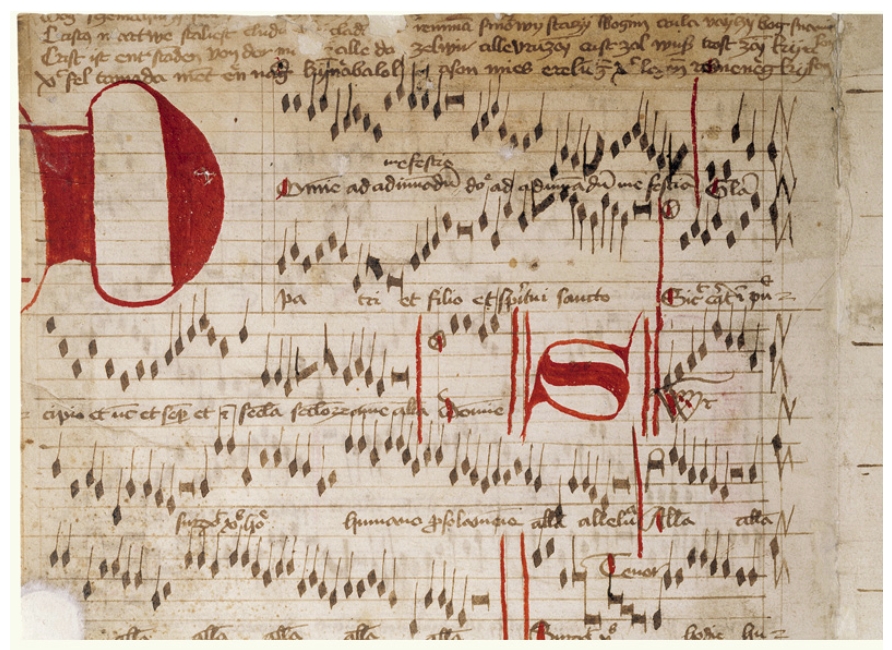

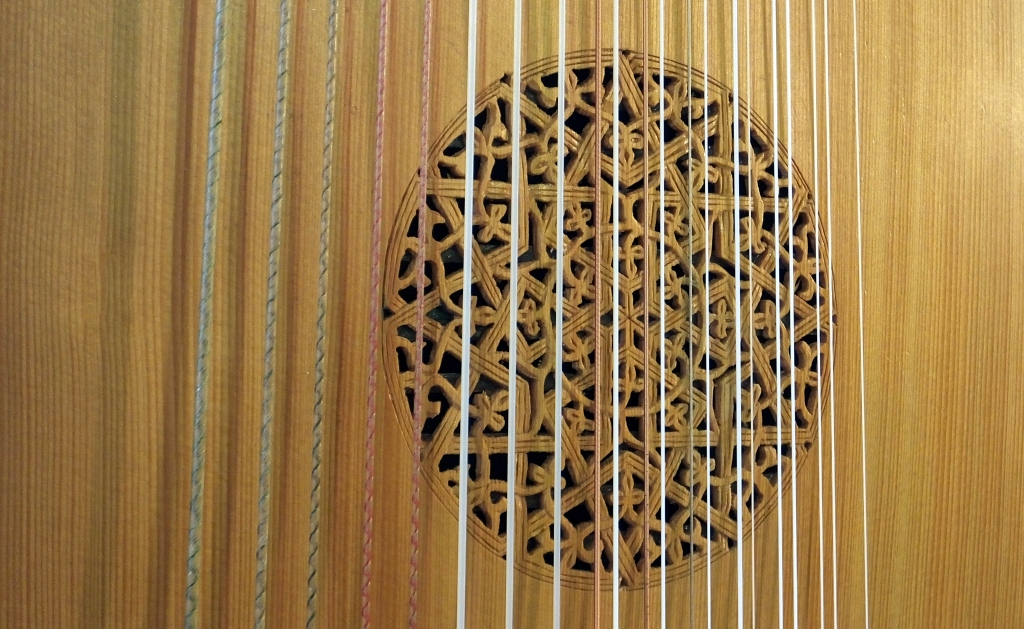

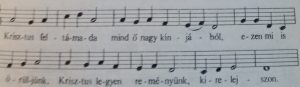

Christ has Risen, a fragment from king Sigismund’s era (1387-1437) – Hans Judenkönig (1450-1526): Christ ist erstanden

Transcription of the fragment with medieval orthography in 4 languages:

Hungarian lyrics:

Krisztus feltámada mind ő nagy kínjából, azon mi is örüljünk, Krisztus legyen reményünk, Kyrie eleison.

Lyrics in English:

Christ has risen from all his great pains, Let us too rejoyce on it, Let Christ be our hope, Kyrie eleison

ARCHLUTE

ARCHLUTE

copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 1999. The original instrument: Wendelin Tieffenbrucker (1551-1611, Padua), Brussels (M.I. No 1563).

This is a recently sent live recording taken from the audience. A few years ago, I played in the chapel hall of the Jesuit “House of Dialogue” in Budapest at the opening of an art exhibition.

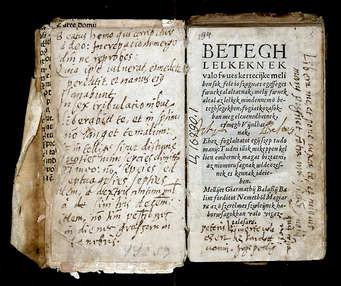

The 14th-century Hungarian lyrics was found in the binding of an ancient Highland (Northern part of Hungary up till 1920) incunabulum since older documents were used by bookbinders to reinforce bookplates. The Hungarian text written in medieval orthography can be seen directly above the sheet music – which by the way is a precious document of the two-voice singing practice of medieval Hungary – on the picture above the media player. The same lyrics in German, Polish and Czech languages are above the Hungarian lines though most of the Czech one fell victim to the bookbinder’s knife. This song is believed by music theorists to have been sung simultaneously in four languages at Easter during the solemn mass:

”Judging from the fragment of the Sigismund period, the Easter hymn ’Christ is risen’ represented the vernacular Easter chant already at the end of the 14th century. A hundred years later, Osvát Laskai mentions in his Gemma Fidei another Easter text sung by Hungarian soldiers before battle: ‘Christus surrexit, mala nostra texit’ (Now that Christ has risen, he washed our sins away).”

Rajeczky Benjamin, Music History of Hungary I, p. 84.

”The earliest surviving example is only one text: ‘Christ is risen from the dead, we too shall rejoice, Christ be our hope, Kyrie eleison’. It is written in Hungarian, German, Czech, Polish, as it might have been known in a town in the Highlands, and it seems that it was sung at the same time, each one in his own language, at Easter. From the state of the text’s language, it is thought that it may be a later legacy of the 14th century. Its melody is also easy to find in contemporary European and later Hungarian music.”

László Dobszay, Hungarian Music History p. 300.

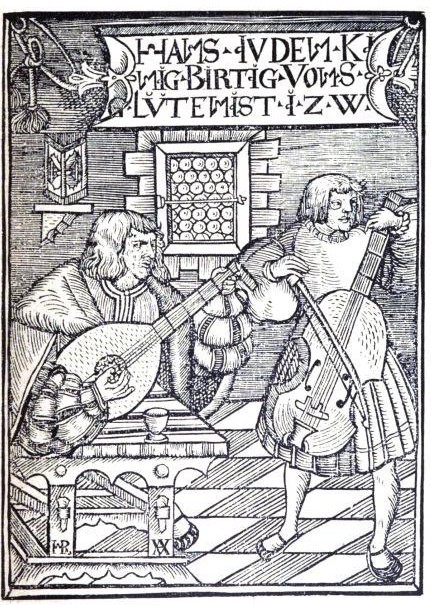

I set the lyrics to the well-known “Christ ist erstanden” melody variant by Hans Judenkönig.

It is possible that the surprising name of the family which can be traced in the Gmünd archives from 1420 to 1477 belonging to the middle class of the guilds derives from the role of the “Jewish king” in an Easter Passion play.

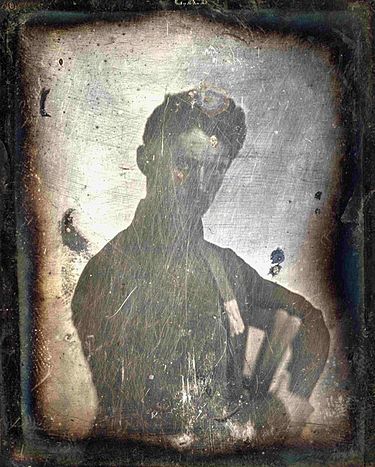

The lute player may be a portrait of Judenkönig himself (woodcut from his “Ain schone kunstliche underweisung”)

Attar: سه پروانه (The Three Butterflies)

جملگی در حکم سه پروانهایم

در جهان عاشقان افسانهایم

اولی خود را به شمع نزدیک کرد

گفت حال من یافتم معنئ عشق

دومی نزدیک شعله بال زد

گفت حال من سوختم در سوز عشق

سومی خود داخل آتش فکند

آری آری این بود معنئ عشق

Mint a három lepke s a gyertya lángja,

Úgy: az ember szíve őt, csak őt vágyja.

Elvakította az elsőt a fény,

S szólt, tudom, mi a szerelem.

Másodiknak szárnyát perzselte a tűz,

S szólt, csak én tudom.

A harmadik a láng szívébe szállt, s elégett.

Ő, csak ő ízlelte meg az egy igaz szerelmet.

translated by

Gábor Domján

Men are like three moths before a candle flame

The first approaches and says

Myself, I know love

The second brushes the flame with its wings and says

Myself, I know the burning of love

The third throws itself into the heart of the flame and is consumed

It alone knows true love

English translation copied from the

booklet of the soundtrack of the film ’Bab ’Aziz’

OUD, عود (Arabic)

Using some parts of three different ouds bought in eastern bazaars, this instrument was rebuilt by Tihamer Romanek with new key- and soundboard.

Attar Farid-ad-din (~1145 – 1221), a Persian poet, one of greatest sufi mystics. This music for the Poem of the Butterflies was written by Armand Amar for the film Bab ’Aziz.

This cover and arrangement for oud accompaniment follows the original music rather freely.

The word ’Attar’ used for poetic pen-name means herbist or apothecary (also rose oil by some dictionaries). Attar was indeed an apothecary in Nishapur, Horasan (today Iran) and he was killed in the massacre committed by the Mongolian troops of Genghis Khan in 1221. According to one of the legends of his death, ’He was captured by a Mongol. One day someone came along and offered a thousand pieces of silver for him. Attar told the Mongol not to sell him for that price since the price was not right. The Mongol accepted Attar’s words and did not sell him. Later, someone else came along and offered a sack of straw for him. Attar told the Mongol to sell him because that was how much he was worth. The Mongolian soldier cut off Attar’s head in revenge.’

John Dowland: Weep you no more, sad fountains

Weep you no more, sad fountains,

What need you flow so fast?

Look how the snowy mountains,

Heav’n’s sun doth gently waste.

But my sun’s heav’nly eyes

View not your weeping,

That now lies sleeping,

Softly, now softly lies sleeping.

But my sun’s heav’nly eyes

View not your weeping,

That now lies sleeping,

Softly, now softly lies sleeping.

Sleep is a reconciling,

A rest that Peace begets:

Doth not the sun rise smiling,

When fair at e’en he sets,

Rest you then, rest, sad eyes,

Melt not in weeping,

While she lies sleeping,

Softly, now softly lies sleeping.

Rest you then, rest, sad eyes,

Melt not in weeping,

While she lies sleeping,

Softly, now softly lies sleeping.

Már elapadj, bús forrás!

Ily fürgén, jaj, ne folyj!

Nézd, havas csúcs vén ormán

Heves Nap mit tékozol!

Ám az én napom kihunyt,

Könny fátylán úszik.

Ő, ki itt nyugszik,

Lágyan, lágyan, oly lágyan, lám, nyugszik.

Ám az én napom kihunyt,

Könny fátylán úszik.

Ő, ki itt nyugszik,

Lágyan, lágyan, oly lágyan, lám, már alszik.

Béke a nyugvás jussa,

Az álom enyhet ád.

Nemde a szép nap újra

Mosolyogva virrad rád.

Könnyebbülj, te is, te szem!

Könnyed mért hullik?

Hisz ő csak alszik,

Lágyan, lágyan, oly lágyan, lám, hogy alszik.

Könnyebbülj, te is, te szem!

Könnyed mért hullik?

Hisz ő csak alszik,

Lágyan, lágyan, oly lágyan, lám, nyugszik.

Hungarian translation by Gábor Domján

ARCHLUTE

copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 1999. The original instrument: Wendelin Tieffenbrucker (1551-1611, Padua), Brussels (M.I. No 1563).

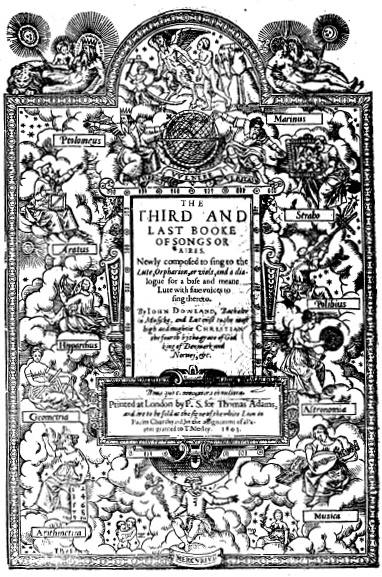

John Dowland First Booke of Songes ( 1597) became an immediate bestseller. It was published at least in five reprints until 1613. Perhaps this success was the reason of his similar song collections that followed (see below: ”The Epistle to the Reader”), in the third of which (The Third and Last Booke of Songes or Aires, 1603) this beautiful enigmatic poem was set to his own music. The author of the poem is unknown, might even be Dowland himself.

If such songs were the ”top hits” of the age that might explain something about how and why audiances were open to Shakespeare’s art, e.g. the Hamlet Soliloquy:

”To die: to sleep; No more”

Bálint Balassi: Borivóknak való (For wine drinkers – sung in English)

BORIVÓKNAK VALÓ

IN LAUDEM VERNI TEMPORIS

az “Fejemet nincsen már” nótájára

Áldott szép Pünkösdnek gyönyörű ideje,

Mindent egészséggel látogató ege,

Hosszú úton járókot könnyebbítő szele!

Te nyitod rózsákot meg illatozásra,

Néma fülemile torkát kiáltásra,

Fákot is te öltöztetsz sokszínű ruhákba.

Néked virágoznak bokrok, szép violák,

Folyó vizek, kutak csak néked tisztulnak,

Az jó hamar lovak is csak benned vigadnak.

Mert fáradság után füremedt tagokat

Szép harmatos fűvel hizlalod azokat,

Új erővel építvén űzéshez inokat.

Sőt még az végbéli jó vitéz katonák,

Az szép szagú mezőt kik széllyel béjárják,

Most azok is vigadnak, s az időt múlatják.

Ki szép füvön lévén bánik jó lovával,

Ki vígan lakozik vitéz barátjával,

Ki penig véres fegyvert tisztíttat csiszárral.

Újul még az föld is mindenütt tetőled,

Tisztul homályából az ég is tevéled,

Minden teremtett állat megindul tebenned.

Ily jó időt érvén Isten kegyelméből,

Dicsérjük szent nevét fejenkint jó szívből,

Igyunk, lakjunk egymással vígan, szeretetből!

Balassi Bálint

FOR WINE DRINKERS

IN LAUDEM VERNI TEMPORIS

To the tune of the song’Fejemet nincsen már’

Blessed sweet Pentecost’s weather brightly glowing,

Beautiful sky on all healthiness bestowing,

Wind that brings relief onto tired wayfarers blowing!

It is thou who givest perfume to the roses,

The once mute nightingale now its song composes,

And trees, too, thou dressest in many-coloured clothes.

It’s through thee that hedges bloom, violets appear;

Flowing waters and wells through thee turn crystal clear,

And our speedy stallions, too, prance along with good cheer.

For after their long run, the tender grass bedews

Their exhausted bodies, while their vigour renews,

Infusing new energy in their nerves and sinews.

And even the good, brave frontier soldiers alight

And through the scented fields roam about with delight,

Now they, too, are overjoyed that the weather’s so bright!

In the soft grass leaving their horses to run free,

With their brothers-in-arms they go off on a spree

While with their blood-stained weapons their pages are busy.

The whole earth is renewed, thanks to thee everywhere.

Thanks to thee, the blue sky breaks through the misty air,

And every living creature emerges from its lair.

Enjoying, as we do, this weather through God’s grace,

From our hearts let us all His holy name praise,

Let us drink, and to true friendship our glasses raise!

English translation

by René Bonnerjea

8 chorus renaissance lute

copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 1998. The original instrument: Hans Frei, 1530 (Wien, KHM C34).

Sometimes I sing this song – of course, in Hungarian to Hungarian audiences – of Bálint Balassi (1554-1594) which has a double – Hungarian and Latin – title : Borivóknak való (For Wine Drinkers) / In laudem verni temporis (In praise of spring-time) dropping stanzas 4, 5 and 6. I do this partly because these are the stanzas having the most of the archaic phrases hard to understand at first for present-day’s ears, but also – maybe subconsciously – because I don’t feel like willing to praise ’ blood-stained weapons’.

Still, I have mixed feelings when I drop these stanzas. And also when I don’t. So I don’t quite agree with myself in either case. This needs to be explained:

The ’good, brave frontier soldiers’ gave their lives for the ’sacred case’ defending Christianity and the homeland. The Turkish soldiers gave their lives to save the souls of their infidel Hungarian brothers for the ’only one faith’. There have been so many causes, faiths, and so much blood has been shed for thousands of years for the lust of power operating with ideologies. An is still being shed today.

In my opinion, this poem is about praising life, and that’s why I sing it. And if I don’t hide the fact that it was chiefly the sword that represented manly virtue for our predecessors in their times and that they were led by their belief in defending the country, it is to give due honour to them and is not some kind of sabre-rattling.

If there are flush meadows of Elysium somewhere, and our ancestors – including Sir Balassi – are galopping around on their ’speedy stallions’ there, I imagine they wish us to stop wars and show manly virtues in defending life instead.

In the ’Balassi-codex’ we find this comment before the poem: ”To the tune of the song ’Fejemet nincsen már’<’No place to lay my head’>”. This confirms the statement I made earlier that in this age poems and songs meant very much the same. This translation is the work of the recently deceased (2012) linguist, poet, literary translator of Hindu-English origin René Bonnerjea who lived in Hungary for forty years and besides holding other posts, was a professor of the prestigious Eötvös College in Budapest. Thanks to Andy Brunning for answering questions about prosody in applying the translation to the original tune.

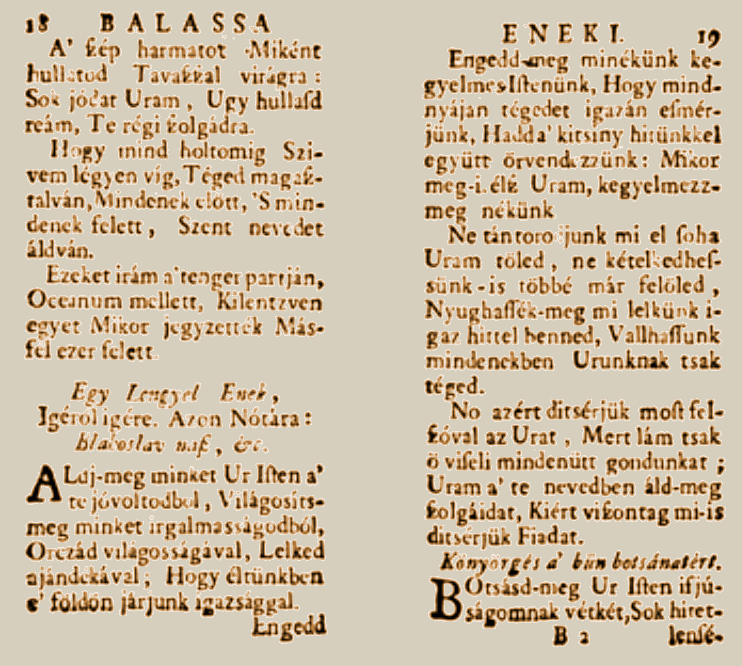

Bálint Balassi: Áldj meg minket Úristen (Bless us Oh Lord Almighty – the first stanza sung in Polish, Hungarian and English)

Jakub Lubelczyk

Psalmus. 67. (68)

Bálint Balassi

“Egy lengyel ének igéről igére és ugyanazon nótára:

Blogosław nas nasz Panie”

Translated by Jeni Melia, Christopher Goodwin and Gábor Domján

Błogosław nas, nasz Panie, z miłosierdzia Twego

Oświeciwszy światłością oblicza swojego

Aby hymny tu na Ziemi znali drogie Twoje

Okaż nam to przed ludźmi miłosierdzie swoje.

Áldj meg minket, Úristen, az te jóvoltodból,

Világosíts meg minket irgalmasságodból

Orcád világosságával, Lelked ajándékával,

Hogy éltünkben ez földön járjunk igazsággal!

Bless us Oh Lord almighty for Thy great benevolence

Illuminate our minds in Thy mercifulness

With bright shining of Thy face and gift of Thy Holy Sprite

So that our lives on this Earth in truth we may live aright.

Niechaj je wyznawają wszyscy narodowie,

A stąd się rozradują i niewiernikowie,

Kiedy Ty swoje wierne w łasce będziesz rządził,

Strzegąc, aby na stronę żaden nie zabłądził.

Engedd meg ezt minekünk, kegyelmes Istenünk,

Hogy mindnyájan tégedet igazán esmérjünk,

Hadd az kicsiny hitűnkkel együtt örvendezzünk,

Mikor megítélsz, Uram, kegyelmezz meg nekünk!

Wysławiajcież już Pana, wysławiajcie, ludzie,

Bo widzicie, jak z ziemie wam pożytek pojdzie.

Ty nas błogosław, Panie, a Twe święte imię

Niech po wszystkich narodach wielkim strachem słynie.

Ne tántorodjunk mi el soha, Uram, Tőled,

Ne kételkedhessünk is többé már Felőled,

Nyughassék meg mi lelkünk igaz hittel Benned,

Vallhassunk mindenekben urunknak csak Téged.

No, azért dicsérjük most felszóval az Urat,

Mert lám, csak ő viseli mindenütt gondunkat,

Uram, az te nevedben áldd meg szolgáidat,

Kiért viszontag mi is dicsérjük Fiadat.

THEORBO, or its less frequently used name nowadays: CHITARRONE

copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 2009. The original instrument: Magno Tieffenbrucker (Venice, 1608), London (RCM 26)

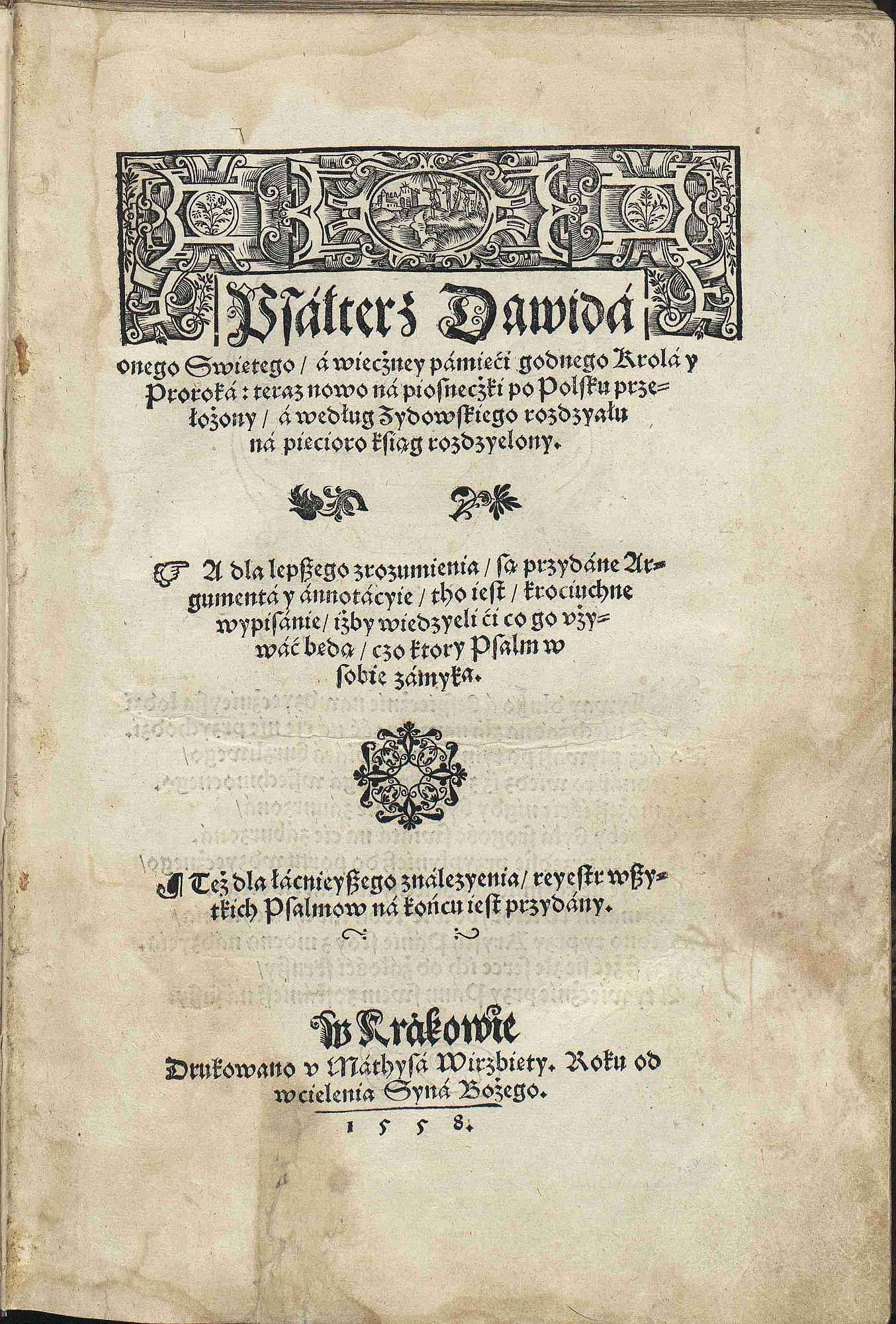

Getting in contact with Calvinistic circles during his stays in Poland, Bálint Balassi got to know and thus translated the song starting with “Błogosław nas nasz, Panie”, a paraphrase of Psalm 67 from the book of Jakub Lubeczyk: Psałterz Dawida (1558). He also added a fourth stanza of his own to his translation. The preamble in his publication literally translates: ”A Polish song from verb to verb. To the tune of Blahoslav nas”.

I sing only the first stanza here in three languages: the original Polish version, Balassi’s Hungarian translation and also an English adaptation. This later one is a joint work with singer Jeni Melia and lutenist Christopher Goodwin secretary of the British Lute Society with whom and with the Kecskés Ensemble we gave some concerts in Poland by the invitation of Polish lute-artist Antoni Pilch in 2009. Grateful thanks to Antoni for his kind invitation and to Jeni and Chris for their co-operation and the tremendous help they gave me in the venture of translating to their native tongue.

As for the imitation of Polish pronounciation besides some native speakers, I owe great gratitude to Polonist Ms Anna Íjjas.

The accompaniment of the song is based on the interpretation of András L. Kecskés.

Two Hungarian folksongs (sung in English – arrangement by Elek Huzella)

1. Where are you my sweetheart (Hová készülsz szívem)

2. Hear the rooster crow (Szól a kakas már)

1.

Hová készülsz szívem

tőlem eltávozni,

tőlem elbujdosni?

Az idegen földön

ki fog téged szánni?

Hogyha megbetegszel,

ki fog hozzád látni?

Megfogott madárhoz

életem hasonló,

életem hasonló.

Napnak fényét látom,

homályba boruló.

Szép gyönyörűségem

naponként elmúló.

2.

Szól a kakas már

Majd megvirrad már

Zöld erdőben, sík mezőben

sétál egy madár.

Micsoda madár,

Micsoda madár,

Zöld a lába, kék a szárnya,

Engem odavár.

Várj madár, várj,

Te csak mindig várj!

Ha az Isten neked rendelt,

Tied leszek már.

1.

Where are you my sweetheart

preparing to part from me,

hiding far from me?

In that distant, strange land

who’ll take pity on thee?

Should you ever fall ill,

who will care for thee?

Like a bird ensnared,

my life dims all going grey,

slowly slipping away.

The Sun gives in to dusk

with each dying ray.

All my sweet delights are

waning day by day.

2.

Hear the rooster crow,

Soon the dawn will glow.

In green forests, in lush meadows

Walks a bird below.

What a bird, so fine!

What a bird, so fine!

Green feet, blue wings, she waits for me,

This lovely bird of mine.

Wait you bird of mine,

Just you wait, oh mine!

If God ordered me for thee,

Then sure I will be thine.

English translation by Gábor Domján

Yamaha „electric classic guitar”, played accoustic

The arrangement of these two folksongs* is the work of contemporary composer Elek Huzella (1915-1971), presumably the 2nd and 3rd pieces of his Four Lovesongs for Voice and Guitar.

’Presumably’ because from the music sheet I once owned, only these two songs survived in photocopy, so being unsure of the source, I can only make probable its title.

Though I made a transcription of the accompaniment for lute as well, I found this 20th century setting – meanwhile accepting the original intention of the composer – more becoming to be played on guitar. Also, I chose a light action, commercial guitar for the purpose since effects like slides for example sound better on it.

An interesting addendum: The 2nd song based on the Messianic symbol of the rooster’s crow and amended with some additional lines in Hebrew became an internationally recognised treasure of Hungarian Judaism.** Here’s a short video from a Purim party I was kindly invited to and where I sang with the guests this version, too.

I always try to get advice from reliable native speakers when translating and novelist Ms Julia Rubin was kind enough to help me translating these songs. I met her in luthier Romanek Tihamer’s workshop. Her new novel touches upon the lost instrument the lute-harpsichord, and travelling by in Europe, she visited Tihamer to hear the sound of his reconstructions of the instrument. I am very grateful to her for the thorough weighing of words and the brilliant pieces of advice she gave me.

* Or lovesongs from the renaissance era? – the lyrics of the first song was found in the 17th century Mátray-Codex, the second one was collected by Zoltán Kodály in 1912 as a folksong, but the provenance of it is widely debated by scholars <unfortunately, all related literature I found is in Hungarian>

** A quote from internet: ’… In particular, Reb Taub is renowned for his own poetic creations – Jewish religious texts set to Hungarian folk melodies of the immediate region, which he often considered to have originated in the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. To cite his most famous example, Reb Taub once heard a shepherd boy in a meadow singing; having recognized the tune as an ancient Jewish melody from the Temple, he paid him two gold pieces for his song. The rabbi instantly learned the melody while the boy forgot it. The song itself, in Hungarian “Szól a kakas már“ (The Rooster is Crowing), remains famous to this day, repeatedly performed and recorded.’

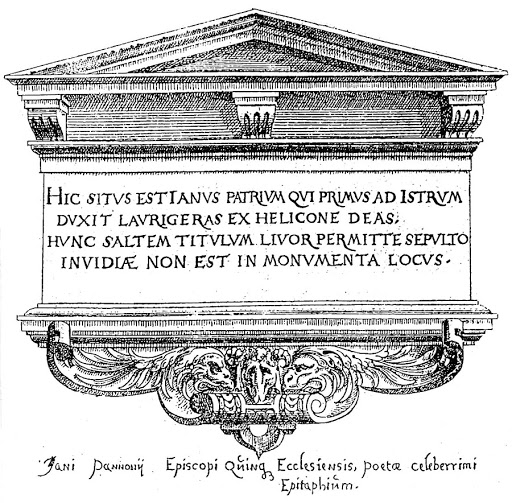

A bilingual (Croatian-Hungarian) traditional folk-song on Janus Pannonius

Croation lyrics

Što to radiš biskupe naš s Medvedgrada,

zar urotu protiv našeg Matijaša?

Kolo pravde zaustavit’ ne možeš,

tamnica če bit’ tvoj stanak dok ne m’reš.

Kad bi pozv’o na prijestolje tog Poljaka,

klade bi nam bila sudba oko vrata.

Hungarije grb će nosit’ tudi svat,

opomena nek nam bude prošlost sva.

Čuj nam molbe gospon Janoš iz Čezmice,

nije krinka urote za tvoje lice,

Nit’ je bodež za čovjeka pravedna,

oružje je pero tvoje – k’o nekada!

Original Hungarian version published by Hugó Borenich

Medvedgrádi püspök urunk, mit csinyáltál,

Amikoron Mátyás ellen áskálódtál?

Ne állítsd meg az igazság kerekit,

Sötét tömlöc lesz itt lakod holtodig.

Mér is hoznál egy polyákot a trónunkra,

Kalodasors szorul akkor a nyakunkra.

Magyar címert ne hordozza idegen,

A múlt rossza legyen néked intelem.

Csezmiczei János arra kérünk téged,

Ármányszövés sose legyen mesterséged.

A gyiloktőr ne gyalázza kezedet,

Penna legyen mindvégig a fegyvered!

Verbatim, non-literary English translation

Our bishop of Medvedgrad, what have you done

Turning against our king Mathias

The rolling of the wheel of truth cannot be stopped

You will dwell in a dark dungeon until you die

Why bring a Pole unto our throne

A pillory-fate would be on our necks then

The Hungarian coat of arms should not go to strangers

Let our sad past be the warning

John of Čezmice, we ask you

Never to indulge in conspiracies

Let not your hand be shamed by the dagger

Let the quill be your only arm until the end

8 chorus renaissance lute

copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 1998. The original instrument: Hans Frei, 1530 (Wien, KHM C34).

A bilingual (Croatian-Hungarian) traditional folk-song on Janus Pannonius

Lute artist András L. Kecskés heard many years ago a historic song sung in Croatian about Janus Pannonius performed by the Croatian folk singer and guzla player Mile Krajina. He had put the melody onto paper right then and there. Later on, he acquired the sheet music of Hugó Borenich as well, a teacher and church organist from Rétfalu (today part of Osijek, Croatia). He summarized it all in his recent letter to me:

“Here I send you the sheet music with chords by Hugó Borenich. I personally prefere the version of Mile Karijena (~as more authentic perhaps?). My story goes back to the 1980-ies when I was invited to give a concert in Szigetvár. There, to my surprise, I performed on the same stage as the fantastic guzlar, the Croatian folk singer, Mile Krajina. Practically, it was a song-dual with the two of us me and Mile Krajina the guzlar his roots of style anchored deep in antiquity. No need to say this “dual” ended with the total failure on my side. Mile sang a harsh and shrill sound resembling the sound of a trumpet (the way it was still heard in the 1950-ies by historic singers in country fairs in Hungary…) Otherwise, Mile considered himself a folk poet, he was introduced like that every occasion on stage. He varied the pieces he performed every time, he even changed the melody at times. We – musicians playing from sheet music – are the victims of this practice going back to antiquity, hence the uncertainty about giving the “correct” tune. The lute accompaniment worked out by me is already imaginable by the turn of the 15th and 16th century… Apart from his songs about the Zrinyi-s and the Hunyadi-s, Mile also performed a historic piece known in Osijek about Janus Pannonius to which H. Borenich attached a few “church organist style” chords* as well in his sheet music. The tune of the historic song on J.P. performed by Mile differs a bit from the one published by H. Borenich…”

In the literature** available by me in Hungary, I found no traces of either the lyrics or the melody, however, the later shows resemblance to the melodies of Sebestyén Tinódi Lantos. After tedious search on net and correspondence with the Croatian Academy of Sciences I could gather the followings about the provenance of the song:

http://real-j.mtak.hu/4901/1/HungarologiaiKozlemenyek_1989_81.pdf

“…for example the recently deceased Hugó Borenich, teacher and reformed church organist of Rétfalu, used to perform his folk-song repertoire accompanying it on organ (even he himself had collected the work-song tradition of Slavonia), … the frequent slurring of the borderline between non-professional and professional opposition is depicted by the typical local figure of Marci Istye who at different occasions such as baptisms, weddings and funeral parties played the role of the professional artist as singer and zither player and apart from his folklore repertoire readily sang popular songs such as the legend of Jelengrad including the love story of the countess and the peasant boy, the Hungarian folk-song on Janus Pannonius, the Zrinyi ballad and the epic about Márkó Sztancsics the captain of Szigetvár…”

Hugó Borenich wrote about his collecting songs in 1933-34 in:

https://www.vamadia.rs/sites/default/files/2020-11/04_Jugoszlaviai_magyar_nepkolteszet_I_.pdf

“… I found the fragment of the folk-song about Janus Pannonius in Budakovác … this is where I became acquainted with Marci Istye (1866-1940), “the man of songs of Szarvasvár”, the legendary figure and keeper of the folk heritage of the Drava river region. It was him who called my attention to the old folks-ong that mentions a bishop. At that time I didn’t know who the song was about even though I could get the tune down form Marci Ištye’s singing. The song fragment found in Budakovác had the same subject-matter. The real final form comes from Kálmán Rumpf teacher of Vörösmart who had the whole text of the folk-song about Janus Pannonius. Combining all these, came to light a so far unknown historic folk-song about the great humanist of the 15th century. It was published together with the short biography of Marci Istye in 1973 in the Review of the academy of Sciences and Arts of Yugoslavia.”

And here is the English abstract of the said review kindly sent to me in PDF by the Academy of Sciences and Arts of Croatia:

It is awe-inspiring that – contrary to endless wars and centuries of Turkish occupation – the folk memory could keep alive an artistic relic of both the Croatian and Hungarian nations for 5-600 years in which our poet is warned against taking part in the plot against King Mathias.

The video recording of the song where I sang the song with introductory and ending lines in Croatian (apologies for my pronunciation where appropriate – my native speaker helper who said it was OK might have been too polite) and the rest with a bit updated Hungarian text can be heard at:

On this site here, I have the sound recording of the full song with alternating Croatian and Hungarian stanzas plus the first 4 lines repeated in Hungarian at the end, all in the original folk version published by Hugó Borenich.

====

* These chords are acually the chords played by Marci Istye, the source from who this song was collected, on his horse headed tambure.

** Yugoslav Folk Music, Serbo-Croatian Folk Songs and Instrumental Pieces from the Milman Parry Collection by Béla Bartók and Albert B. Lord, Vol. I-IV.

Publications of the Milman Parry Collection, Serbo-Croatian Heroic Songs, General Editor: Albert B. Lord, Vol. III & XIV.

Bodor Anikó: Vajdasági magyar népdalok, Vol. I-III.

Paksa Katalin – Németh István: Muravidéki magyar népzene

Romance de la pérdida de Alhama (The siege and conquest of Alhama)

ROMANCE DE LA PÉRDIDA

DE ALHAMA

Paseábase el rey moro

— por la ciudad de Granada

desde la puerta de Elvira

— hasta la de Vivarrambla.

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!—

Cartas le fueron venidas

— que Alhama era ganada.

Las cartas echó en el fuego

— y al mensajero matara,

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!—

Descabalga de una mula,

— y en un caballo cabalga;

por el Zacatín arriba

— subido se había al Alhambra.

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!—

Como en el Alhambra estuvo,

— al mismo punto mandaba

que se toquen sus trompetas,

— sus añafiles de plata.

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!—

Y que las cajas de guerra

— apriesa toquen el arma,

porque lo oigan sus moros,

— los de la vega y Granada.

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!— . .

Los moros, que el son oyeron

— que al sangriento Marte llama,

uno a uno y dos a dos

— juntado se ha gran batalla.

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!—

Allí habló un moro viejo,

— de esta manera hablara:

—¿Para qué nos llamas, rey?

— ¿Para qué es esta llamada?

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!—

—Habéis de saber, amigos,

— una nueva desdichada:

que cristianos de braveza

— ya nos han ganado Alhama.

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!—

Allí habló un alfaquí

— de barba crecida y cana:

—Bien se te emplea, buen rey,

— buen rey, bien se te empleara.

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!—

Mataste los Bencerrajes,

— que eran la flor de Granada,

cogiste los tornadizos

— de Córdoba la nombrada.

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!—

Por eso mereces, rey,

— una pena muy doblada:

que te pierdas tú y el reino,

— y aquí se pierda Granada.

—¡Ay de mi Alhama!—

ALHAMA VESZTÉNEK

BALLADÁJA

Föl-le jár a mór király,

Öszvérét vágtára fogja,

Granadának városában

Folyton-folyvást hajtogatja:

Jaj nekem Alhama!

Levél jött: Alhama elveszett,

Baljós jel papírra róva.

Tűzben ég az átkozott levél,

És a hírnök feje hull a porba.

Jaj nekem Alhama!

Öszvérhátról ló nyergébe száll,

S vágtat föl a vár fokára,

Zacatin utcáin át,

Föl, hol fénylik az ékes Alhambra,

Jaj nekem Alhama!

És hogy a fellegvár fokára hág,

Rögvest száll harsány parancsa:

– Mind az összes ezüst trombita

Harsogva hívja népem hadba!

Jaj nekem Alhama!

Zúgjon minden harci dob,

Dübörögjön harci lárma,

Hallja minden mór e zajt,

S fegyvert fogva jöjjön már ma!

Jaj nekem Alhama!

Hallván hall a tenger mór vitéz,

Véres Mars hívását hallja,

Jön már egy, jön két, jön számtalan,

S nőttön nő a had hatalmasra.

Jaj nekem Alhama!

S kiáll a mórok egyik véne,

Illő módon ekként szólva:

– Mért e hívás ó király?

Mért e hívás, mondd, a hadba?

Jaj nekem Alhama!

Halljátok barátim mind a szörnyű hírt!

Odalett a végső várta.

Vad, merész keresztény kardtól

Esett el Alhama vára.

Jaj nekem Alhama!

S előáll az ősz alfaqui,

Szeme izzó szén, bár hó szakálla,

Azt kapod, mi néked jár király,

Azt kapod, mi már régen járna.

Jaj nekem Alhama!

Leöletted a Benszerráh családot,

Derékba tört Granada termő ága.

S tűrtél cifra Cordovából

Hitszegőket népünk romlására.

Jaj nekem Alhama!

Így hát mindezért király

Többször sújt rád végzet kardja:

Koronádra, Granadádra,

Tieidre, s tenmagadra.

Jaj nekem Alhama!

THE SIEGE AND CONQUEST

OF ALHAMA

The Moorish King rides up and down,

Through Granada’s royal town;

From Elvira’s gate to those

Of Bivarambla on he goes.

Woe is me, Alhama!

Letters to the monarch tell

How Alhama’s city fell:

In the fire the scroll he threw,

And the messenger he slew.

Woe is me, Alhama!

He quits his mule, and mounts his horse,

And through the street directs his course;

Through the street of Zacatin

To the Alhambra spurring in.

Woe is me, Alhama!

When the Alhambra walls he gain’d,

On the moment he ordain’d

That the trumpet straight should sound

With the silver clarion round.

Woe is me, Alhama!

And when the hollow drums of war

Beat the loud alarm afar,

That the Moors of town and plain

Might answer to the martial strain.

Woe is me, Alhama!

Then the Moors, by this aware,

That bloody Mars recall’d them there,

One by one, and two by two,

To a mighty squadron grew.

Woe is me, Alhama!

Out then spake an aged Moor

In these words the king before,

‘Wherefore call on us, oh King?

What may mean this gathering?’

Woe is me, Alhama!

‘Friends! ye have, alas! to know

Of a most disastrous blow;

That the Christians, stern and bold,

Have obtain’d Alhama’s hold.’

Woe is me, Alhama!

Out then spake old Alfaqui,

With his beard so white to see,

‘Good King! thou art justly served,

Good King! this thou hast deserved.

Woe is me, Alhama!

‘By thee were slain, in evil hour,

The Abencerrage, Granada’s flower;

And strangers were received by thee

Of Cordova the Chivalry.

Woe is me, Alhama!

‘And for this, oh King! is sent

On thee a double chastisement:

Thee and thine, thy crown and realm,

One last wreck shall overwhelm.

Woe is me, Alhama!

Hungarian translation

by Gábor Domján

English translation

by Lord Byron

VIHUELA

copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 2013. The original instrument: „Quito vihuela” (Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús, Quito, Ecuador).

.

The ballad ”Paseábase el rey moro” was translated from Arabic into Spanish (though doubted by some scholars if an Arabic version had existed at all) by Perez de Hita (1544-1619) in his historical novel (Historia de los vandos de los Zegríes y Abencerrages (1595–1619), or Guerras civiles de Granada). The ballad tells the story of the loss of Alhama, the last Moorish fortress before Granada, in 1482. Perez de Hita writes in his book: “The Count of Tendilla (who became the governer of Granada after having defeated the Moors) felt obliged to prohibit this ballad because it stirred up the populace to such a degree as to disturb the peace and make it necessary to resort to armas in order to stifle the mutinies of the Moriscos .” The music is written for vihuela by Luis de Narváez („Los seys libros del Delphín, de música cifras para tañer vihuela”, 1538: Romance <<Paseávase el Rey moro>>, del quarto tono). Neither the original Arabic poem nor it’s tune survived, however, I play some beats at the beginning of a supposed ”original” version before I start Narváez’s accompaniment as a prelude.

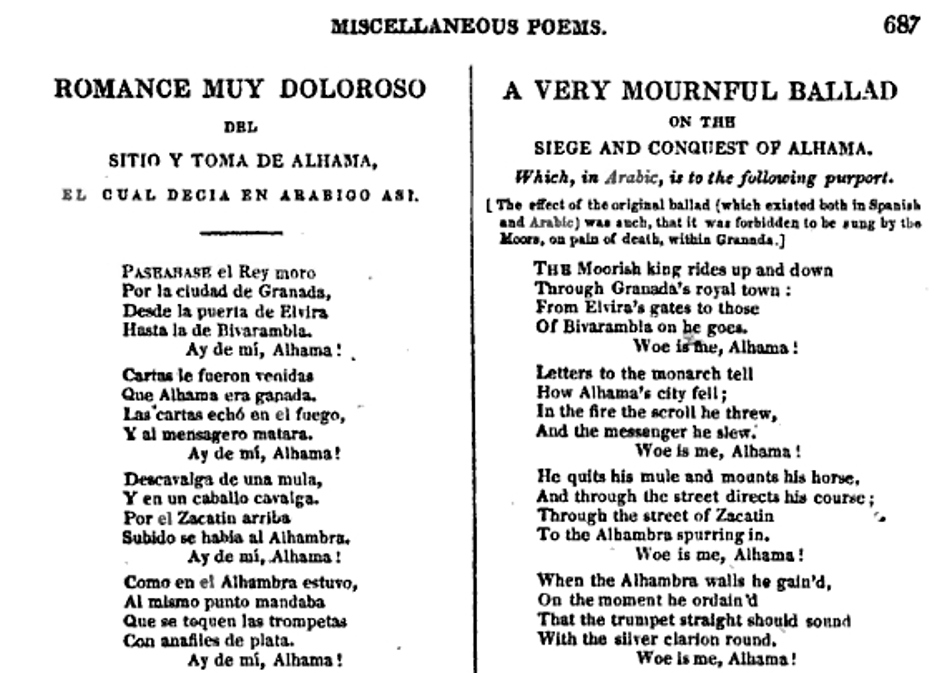

The ballad was translated by Lord Byron, too. Here are the fist few stanzas of it from an early publication:

Luis de Milán: Sospirastes Baldovinos

Sospirastes Baldovinos

Las cosas que yo mas quería,

O teneys miedo á los moros

O en Francia teneys amiga

No tengo miedo á los moros

Ni en Francia tengo amiga

Mas tu mora y yo cristiano

Hazemos muy mala vida

Si te vas conmigo en Francia

Todo nos será alegria:

Haré justas y torneos

Por servirte cada’l dia

Y verás la flor del mundo

De mejor cavalleria:

Yo seré tu cavallero

Tu serás mi linda amiga

Vágyad súgja sóhajtásod

Válasz rá ím, szemem könnye,

Vagy tán féled népemet, a mórt,

Vagy Frankföldön él tán szíved hölgye?

Nem, nem félek senki mórtól,

Frankok közt sincs az én szerelmem,

Ám te mór vagy, és keresztény én,

Hogy élhetnénk itt mi ketten békességben?

Ám, ha eljönnél vélem Frankföldre,

Várna ránk ott végre áldott béke,

Bajvívásban érted megküzdnék

S szolgálnálak éjt nappá téve.

Jöjj! Vár ránk Frankföldnek sok szép virága

Bajnokoknak éke, színe, dísze.

Büszke lész rám, hű lovagodra,

S lész te hölgyem, szívem drága kincse.

Translation by

GáborDomján

You sighed out Baldovinos

All I would like the most

Or are you afraid of the Moors?

Or do you have a girlfriend in France?

No, I’m not afraid of the Moors

And I don’t have a girlfriend in France

But you being a Moor woman and me a Christian man

We would have a very bad life.

But f you come with me to France

There will be happiness for us

I will joust and fight in knightly tournaments

To serve you every day.

You will see the flowers of the world

The best ones of knighthood

I shall be your knight

And you shall be my beloved lady.

(non-literary, verbatim translation)

DESCANT LUTE

Built by: Bernd Holzgruber (’Wien 1979’)

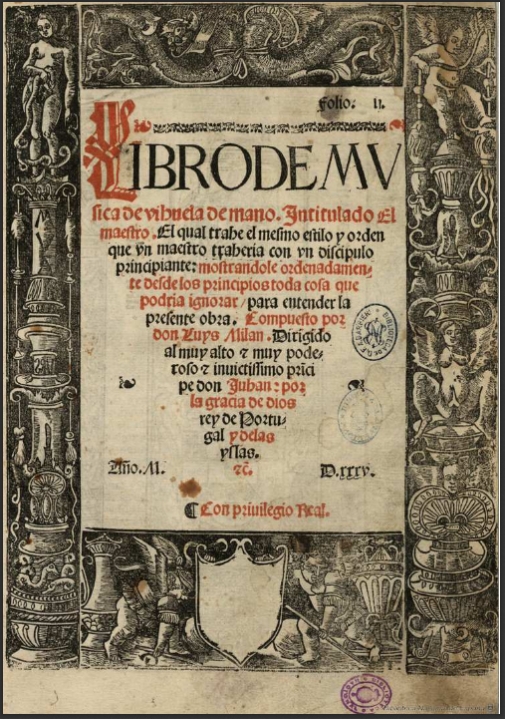

This romance is a lyrical love-song, a dialogue, written by Luis de Milán (~1500-~1561) in his Libro de música de vihuela de mano; Intitulado El Maestro (1536) which was the first vihuela publication in the 16th century.

The vihuela was the popular version of the lute in Spain. Its shape resembles the guitar though it’s light structure and tuning follows the lute. My vihuela is tuned as: e’e’, bb, f# f#, dd, AA, EE, but sometimes I tune it down a full or a semitone for singing purposes. There’s a remark in a contemporary script saying that transposing the accompaniment to fit the singer’s vocal range should be avoided. It is advised to pick an appropriate size and accordingly tuned vihuela instead, one that fits the singer’s voice. Having only one vihuela, the choice was to retune it, but even that didn’t help in distinguishably but still acceptably sing the female and male parts in the dialogue so I chose a descant lute for the accompaniment instead.

Luis de Milán: Falai miña amor

Falai, miña amor,

falai me

Si no me fallays,

matay me, matay me

Falai, miña amor,

queos faço saber

Si no me fallays

que nan teño ser

Pois te neys poder,

falai me

Si no me fallays,

matay me, matay me

Talk my love,

talk to me

If you don’t talk to me,

then kill me, kill me

Talk my love,

Let them know

If you don’t talk to me,

there’s no pont in living

It is in your power

to talk to me

If you don’t talk to me,

then kill me, kill me

(non-literary, verbatim translation)

Szóljál, szívem, szólj,

vagy ölj meg,

Ha nem szólsz,

hát ölj meg, úgy öljél meg!

Szóljál, szívem, szólj,

hadd tudják mind meg!

Ha nem szólsz hozzám,

Mért éljek, mért is éljek?

Csak egy szót kérek,

vagy ölj meg,

Ha nem szólsz hozzám,

Ölj meg, hát öljél meg!

Fordította: Domján Gábor

VIHUELA

copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 2013. The original instrument: „Quito vihuela” (Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús, Quito, Ecuador).

.

This Portuguese or Gallego villancico (song) is from Luis de Milán’s (~1500-~1561) Libro de música de vihuela de mano; Intitulado El Maestro (1536).

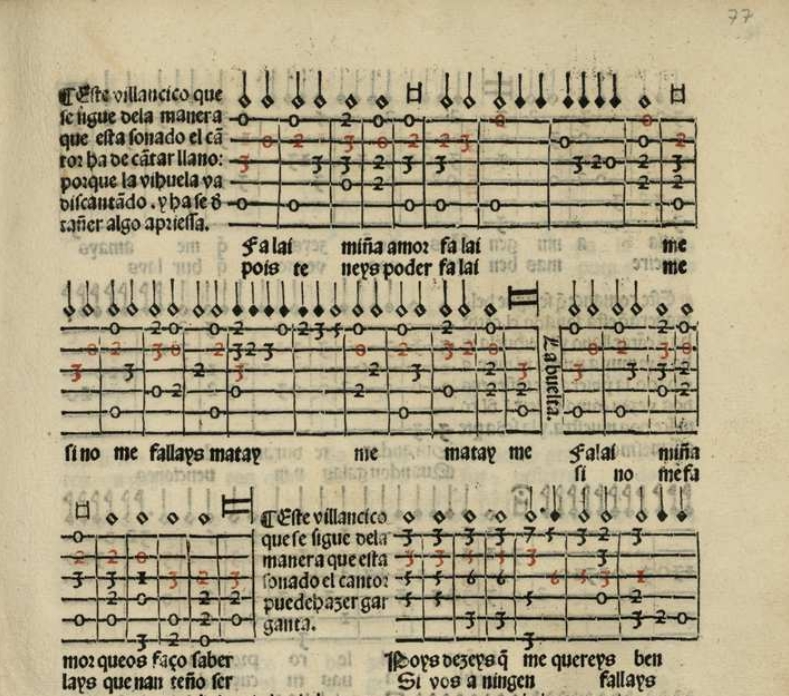

The engraving next to the MP3 player depicts Orpheus playing the vihuela from the above book. The picture under it shows the tablature of the song with the tune to be sung printed in red.

An early 17th century Spanish author writes about the vihuela:

“This instrument has been held in great esteem until our own times, and there have been excellent players; but since the invention of the guitars there are very few who apply themselves to the study of the vihuela. This is a great loss, because every kind of notated music can be put on to it, and now the guitar is nothing but a cow-bell, so easy to play, especially when strummed, that there is not a stable-boy who is not a musician of the guitar.”

Though I translated the poem, concerning its message, there’s no point in singing more than one initial line of it in Hungarian. Even that only for fun once the site is supposed to be about translations. However, it is quite lofty to sing in medieval Gallego, the temptation of which I couldn’t resist. My grateful thanks to Ms Laura Lukács literary translator for her help in phonetics, prosody and semantics of the Spanish and Portuguese texts.

One more word about the poem: Luis de Milán was also a poet, but his merit as a poet I cannot judge. However, the most famous Valencian poet of the time Fernández de Heredia advised Milán „to stick with the only art of which he was a master, vihuela playing”.

Lord Byron: So, we’ll go no more a-roving

So, we’ll go no more a-roving

So late into the night,

Though the heart be still as loving,

And the moon be still as bright.

For the sword outwears its sheath,

And the soul wears out the breast,

And the heart must pause to breathe,

And love itself have rest.

Though the night was made for loving,

And the day returns too soon,

Yet we’ll go no more a-roving

By the light of the moon.

Hát mi már nem kóborlunk többé

Oly késő éjeken át,

Bár a szív még szerelemtől terhes,

És a holdfény is árad ránk.

Mert a kard túléli tokját,

S a lélek a lélegzetet,

Álljt mond a szív is, úgy dobban,

Ellobban a láng, kell a csend.

Bár az éj szerelemre termett,

S olyan gyorsan feljön a Nap,

Soha már nem kóborlunk többé

A fénylő Hold alatt.

Hungarian translation by Gábor Domján

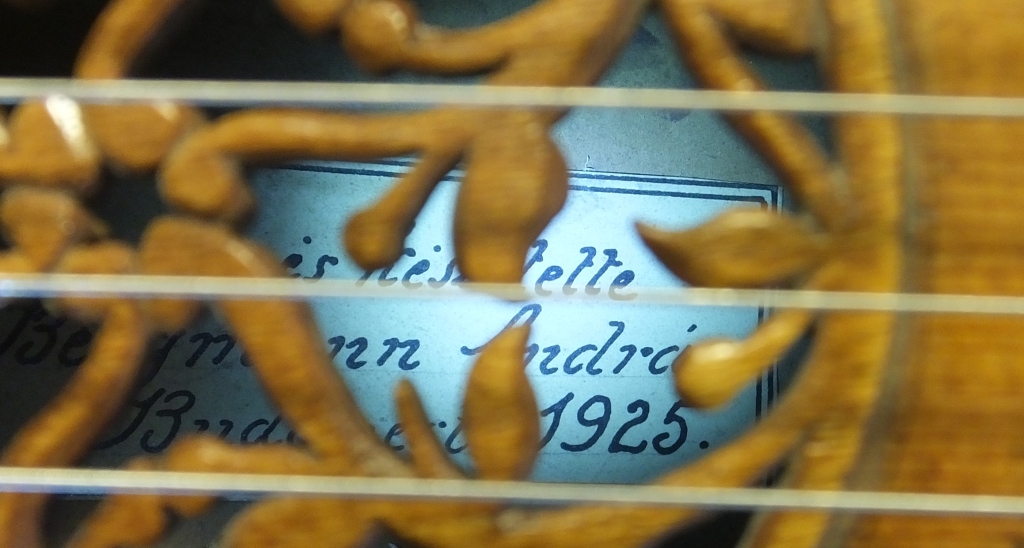

LUTE-GUITAR,

planned and built by András Bergmann Jr. in Budapest in 1925

This poem of Lord Byron was set to music by Richard Dyer-Bennet. I first heard it sung by Joan Baez in the early seventies. I follow here the original accompaniment with minimal differences on a lute guitar tuned to d/a/f/c/G/C. I felt this instrument fits best the romantic poem and song.

At least visually.

Addendum: A contemporary composer (unfortunately forgot the name) wrote a duo for lute and bagpipe. When he was criticized for the lute being non-audible due to the bagpipe, his answer was something like this: It is deliberately so. I wanted to draw attention to the importance of the neglected visual aspect of music.

Some other personal addendum: Finishing recording this song a couple of times, being hungry and searching for a restaurant ’so late in the night’, friend Tamás and I found ourselves in the streets of Budapest ’a-roving by the light of the moon’.

Sándor Petőfi: I’ll be a tree (Fa leszek, ha… – Sung in English)

Fa leszek, ha…

Fa leszek, ha fának vagy virága.

Ha harmat vagy: én virág leszek.

Harmat leszek, ha te napsugár vagy…

Csak, hogy lényink egyesüljenek.

Ha, leányka, te vagy a mennyország:

Akkor én csillaggá változom.

Ha, leányka, te vagy a pokol: (hogy

Egyesüljünk) én elkárhozom.

Sándor Petőfi

I’ll be a tree…

I’ll be a tree, if you are its flowers,

Or a flower, if you are the dew;

I’ll be the dew, if you are the sunbeam,

Only to be united with you.

My little girl, if you are the heaven

I shall be a star above on high;

My little girl, if you are hell-fire,

To unite us, damned I shall die.

English translation by:

C. F. Bowring (questionable, see notes)

This translation is from the volume ‘Hundred Hungarian Poems’, wherein C. F. Bowring is given as the translator of this poem written by Sándor (Alexander) Petőfi. I could find no data about C. F. Bowring, neither online nor in libraries. However, I did find a Sir John Bowring and his version of this poem included in his translations of Petőfi (see picture). He was Petőfi’s first famous contemporary translator. Would the occurrence of identical surnames be a coincidence? Or does C. F. stand for cf. (Latin: confer / conferatur), and therefore could the translator of the poem be the work of the editor of the anthology (Tamás Kabdebó) or someone else, based on Sir John Bowring’s translation? I give up.

Whoever the translator of this poem may be, I, too have made some changes in it. As for my ‘liberty of performance’ (cf. ‘poetic licence’): several poems of Petőfi’s have actually turned into folk songs and a word here or there might have changed in the folk-ed versions as well.

The tune is the composition of Árpád Balázs (1874-1941), a well known composer of his time. I present the song here following the harmonization of lute and guitar artist András L. Kecskés. In his opinion, the melody itself is of Schubertian value.

My friend Tamás had an animated short film made to this love song with a Brazilian graphic designer.

Ophelia’s lament – Shakespeare: Hamlet (act 4, sceen 5)

How should I your true love know

From another one?

By his cockle hat and staff,

And his sandal shoon.

He is dead and gone, lady,

He is dead and gone;

At his head a grass-green turf,

At his heels a stone.

White his shroud as the mountain snow,

Larded vith sweet flowers;

Which bewept to the grave did go

With true love showers

Hogy lehetne felismerni,

Melyik ö, igaz szerelmed?

Kis kalapjáról, botjáról,

Saruban mint megy.

Elment már hölgyem, meghalt már,

Elment már, meghalt ő.

Feje táján fűcsomó,

Lábánál egy kő.

Hófehér, mint a hegytető,

Virágokkal véres,

Könnyel áztatott szemfedő,

Sírban már a kedves.

Hungarian translation by Gábor Domján

DESCANT LUTE

Built by: Bernd Holzgruber (’Wien 1979’)

Found the LP (Fallen Asleep Just Like Papa) of our once favourite group (OPO) on youtube we haven’t heard for decades and made this rendering of Ophelia’s song from it as a last minute birthday present for my wife (Hungarian translation & recording the night before). The original version has a beautifully elaborated version of the theme on 4 or 5 instruments which I couldn’t imitate on a single descant lute, thus this little intermezzo instead before repeating the first stanza.

To be or not to be – Shakespeare, Hamlet Soliloquy, music by Cesare Morelli (sung in Hungarian)

To be; or not to be; that’s the Question.

Whether’t be nobler in the mind;

to suffer the slings and arrows

of outrageous fortune; or to take arms

against a sea of trouble, and by opposing end them?

To die; to sleep; Noe more.

And by a sleep to say wee end the Heartake,

and the thousand nat’rall shocks the flesh is Heir to,

is a consummation devoutly to be wished.

To die; to sleep. To sleep; perchance to dream;

I, there’s the rubb. For in that sleep of death,

what dreames may come;

when we have shuffled off this mortall Coyle,

must give us Pause. There’s the respect,

that makes Calamity of so long life.

For who would bear, the whipps and scorns of Time,

the Oppresour’s wrong, the poor man’s Contumelys,

the pangs of despis’d Love, the Law’s delays,

the Insolence of office, and the spurns

that patient Meritt of the unworthy takes,

when hee himself might his Quietus make,

with a bare Bodkin? Who would these fardles bear,

to groan and sweat under a weary life,

but that the dread of something after death,

that undiscover’d Country, from whose Borne

no Traveller returns, puzzles the will, and makes us

rather bear, those Ills wee have, than flie

to others that we know not of?

Thus, Conscience makes Cowards of us all;

and thus, the native Hue of Resolution,

is sickly’d o’re with the pale Caste of Thought;

and Enterprizes of greatest Pith and Moment,

with this reguard, their Currents turn awry,

and Loose the name of Action.

Text variant from the ayre of Cesare Morelli’s sheet music

Hogy lenni, vagy inkább nem lenni? Ez a kérdés.

Mi az, mi embervolthoz méltóbb,

viselni tán a vak sors csapásait,

csak tűrni? Vagy inkább fegyvert fogni,

szembeszállni, véget vetni tenger kínnak?

A halál csak alvás — nem más.

És ettől végre nyugszik fájó szívünk,

véget ér az ezer nyűg, mi létünk jussa:

Az elhálás, a nász, mit vágyva vágyni kell.

A halál csak alvás, s az alvás álmot hoz tán.

Jaj! Itt a gond. A halál álma

még mit tartogat?

Levetni, hogyha kell, e porhüvelyt,

megálljt ez mond. Ez az a rettenet,

mitől a kínos földi lét oly hosszan tart.

Az évek kíméletlen, kínzó ostorát,

a zsarnok elnyomást, sok önhitt, pimasz frátert,

a viszonzatlan szerelmet, a jogtiprást,

a hivatali önkényt, s hogy a tisztességre

köpnek, mindezt ki tűrné el,

ha önmagának máris békét adhat?

Csak egy éles tőr kell! Kí tűrne létnyomort,

ki hordana izzadva terhet itt,

hacsak e kín, a rettegés, a félsz

az ismeretlen hontól, ahonnét még

utas meg nem tért, nem fékezi?

Hát így választjuk mind az ismerősebb rosszat,

semmint egy ismeretlen mást.

Lám, gyáva, mert fontolgat az ember,

és a biztos válasz tiszta színét

így mossa szét a szürke ráció,

a büszke s bátor pillanat döntései

így válnak köddé, belőlük így lesz

nagy tett helyett nagy semmi.

translated by Gábor Domján

Baroque guitar (vihuela strung as 5 course baroque guitar)

VIHUELA

copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 2013. The original instrument: „Quito vihuela” (Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús, Quito, Ecuador).

.

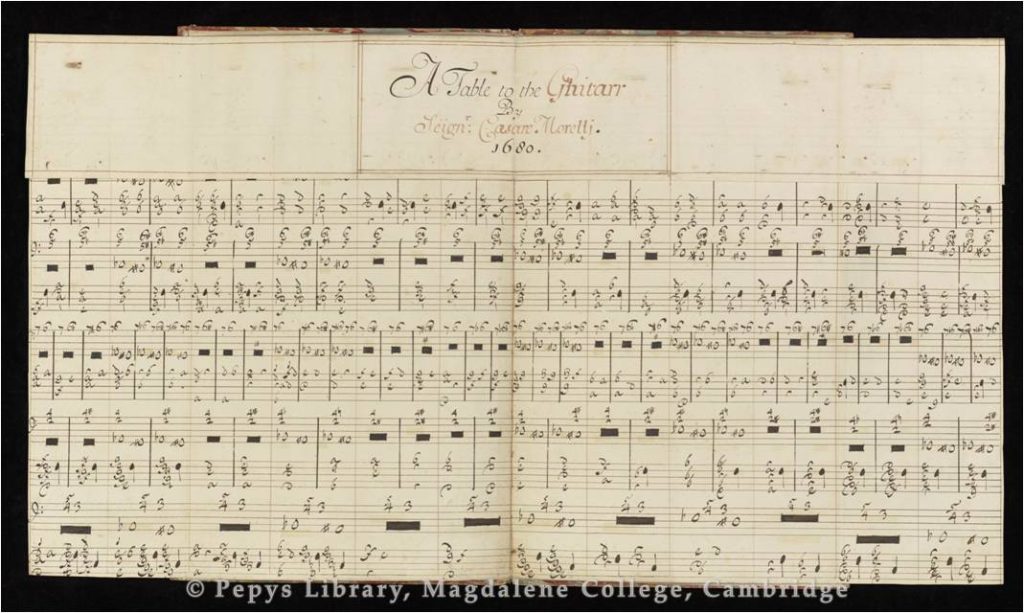

Samuel Pepys, famous for his cryptograph diary of contemporary historical value, had his favourite poems set to music by his own household composer and guitar teacher Cesare Morelli. The manuscript MS 2591 at Magdalena College, Cambridge, contains 51 of these works, including Shakespeare’s famous Hamlet soliloquy.

In 1667, Pepys still wrote on the baroque guitar in this way:

„I there espied Seignor Francisco tuning his Gittar, and Monsieur De Puy with him, who did make him play to me: which he did most admirably, so well I was mightily troubled that all that pains should have been taken upon so bad an instrument.”

Later on, when King Charles the second was learning to play the guitar, this 5 course instrument came into fashion and then in 1675 Cesare Morelli, a Catholic musician who was then living in Portugal, was put into the service of Samuel Pepys in England. His Catholicism and his refusal to enter the Anglican Church caused Pepys serious problems. For the first time, in 1678, all Catholics were banished 30 miles from London. At that time Pepys kept in touch with his household musician by letters, which may have had something to do with his own imprisonment shortly afterwards. It was only after his release that he was sometimes able to take guitar lessons in person from his esteemed master who by regulation had to live in the countryside. Pepys was thus most likely unable to acquire any particular virtuosity on the baroque guitar as Morelli left England in 1682.

About my presentation:

My aim was not to give a historically authentic presentation. If so, it would have to be more opera-aria-like sounding I believe. Also, the accompaniment could certainly have sounded far more elaborate if – let’s say – Morelli had played and Pepys had sung the song. Several of these more “authentic” performances can be found on youtube. Apart from wanting to give my own interpretation of the work in Hungarian, I was also concerned – as Pepys probably was – to put a simple, amateur guitarist’s like accompaniment to the song. Morelli, perhaps keeping Pepys’ abilities in mind, indicated only chords and their strumming up or down in the tablature. That’s pretty much what I did.

About the translation:

I would rather call it a paraphrase of a song lyric. My primary concern was singability. The musical arrangement dictates where and what should be heard from the original text. It was important for me to stick to this trying to keep the original melody and rhythm as much as possible. (At some points it was impossible as Hungarian words are about 30% longer than English ones, which is why our famous 19th c. poet János Arany translated the 35-line Hamlet monologue in 37 lines, for example.)

On this site which was meant to be made for translations chiefly, you can listen to the Hungarian version only, but I have recorded the original English version as well. This can be found separately here.

O Mistress Mine, song from Shakespeare’s Twefth Night (music: Thomas Morley)

William Shakespeare

Thomas Morley

O Mistress mine

O Mistress mine, where are you roaming?

O Mistress mine, where are you roaming?

O, stay and hear; your true love’s coming,

O, stay and hear; your true love’s coming,

That can sing both high and low:

Trip no further, pretty sweeting;

Journeys end in lovers meeting,

Every wise man’s son doth know.

Trip no further, pretty sweeting;

Journeys end in lovers meeting,

Every wise man’s son doth know.

What is love? ‘Tis not hereafter;

What is love? ‘Tis not hereafter;

Present mirth hath present laughter;

Present mirth hath present laughter;

What’s to come is still unsure:

In delay there lies not plenty;

Then, come kiss me, sweet and twenty,

Youth’s a stuff will not endure.

In delay there lies not plenty;

Then, come kiss me, sweet and twenty,

Youth’s a stuff will not endure.

Ó, drága hölgyem

Ó, drága hölgyem, merre, merre?

Ó, drága hölgyem, csak erre, erre!

Itt jő már – hallga! – hív szerelme,

Ím, jő már – hallga! – hív szerelme,

Hangja cseng itt fenn s zeng lenn.

Tovább egy lépést, egy tapodtat se,

Hisz minden útnak egy a vége:

Szívre lel a szív, szívem.

Tovább – ó édes – egy tapodtat se,

Hisz minden útnak egyszer vége,

Célba ért már kedvesem.

A szerelem itt van, azt volt nincs,

A szerelem ma itt van, azt volt nincs,

A boldog perc, csak az legyen kincs,

A boldog perc, hát az legyen kincs,

Ki tudja, meddig tart a nyár.

Virág, ha nyílik, el is szárad,

Hát most adj csókot, add a szádat,

Az ifjúság oly gyorsan száll.

Virág, ha nyílik, el is szárad,

Hát adsza csókot, mindjárt százat,

Az ifjúság – hipp-hopp – elszáll.

Hungarian translation by Gabor Domjan

DESCANT LUTE

Built by: Bernd Holzgruber (’Wien 1979’)

11 course renaissance lute

Copy built by Tihamer Romanek in 2008. The original instrument: Hans Burkholtzer (1596), revamped by Thomas Edlinger (1705), Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum (SAM 44).

This joyful comedy of Shakespeare allows for lots of fun and humor, so I thought, and dared to sing it accordingly both in English and in Hungarian.